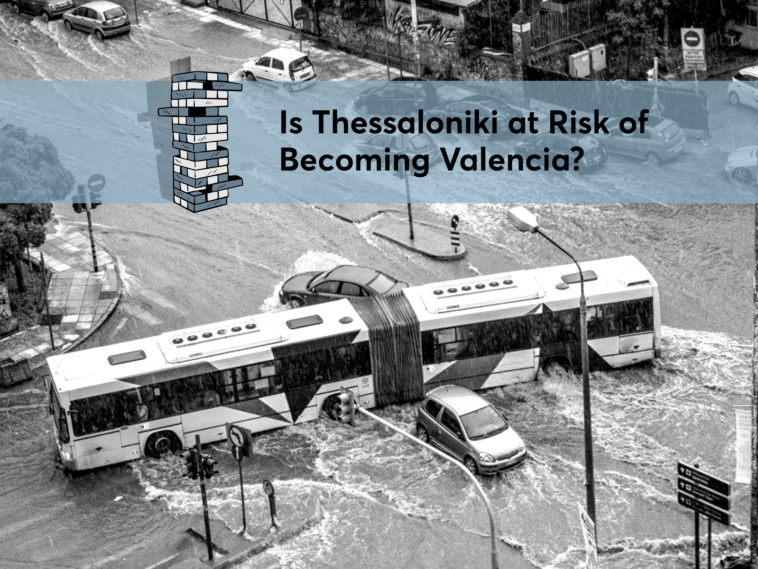

The climate crisis, aside from causing extreme heat, also brings intense and widespread rainfall that occurs in a matter of minutes. The recent tragic flood in Valencia, resulting in over 200 deaths, as well as the floods in Thessaly in the summer of 2023, remind us that the way cities are built and human activities are structured cannot withstand such weather phenomena.

The images of flooded areas in Valencia, Thessaly, Mandra, and elsewhere that we’ve all seen on the news, understandably raise concerns for citizens about whether their city or village can endure such events. At the same time, these increasingly common phenomena should urge the central government and local authorities into taking action before it is too late, which is what happens all too often.

As part of our journalistic research, we examine Thessaloniki’s flood protection preparedness. While responsibilities, such as cleaning water channels, are often shuffled between authorities during crises, it is clear that the Region of Central Macedonia holds a central role in Thessaloniki’s flood defense. The recently approved Regional Climate Change Adaptation Plan (RCCAP) clearly outlines this responsibility. However, the question remains: how effectively is this plan being implemented to safeguard the city from flooding?

As stated to Alterthess by Cristina Macnea ((The interview with Cristina Macnea took place in July 2024)) a chemical engineer with a postgraduate degree in Environmental Infrastructure Project Design and an employee of the Region of Central Macedonia (RCM), the Region plays a pivotal role in addressing and adapting to climate change. The Region is responsible for drafting the Regional Climate Change Adaptation Plan, which includes actions aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change, reducing air pollution, promoting sustainable development, and more. In Central Macedonia, the RCCAP was approved in November 2022, but since then, almost none of the projects it includes have been implemented.

According to Ms. Macnea, the Region is addressing the issue of cleaning water channels incorrectly, with piecemeal efforts rather than comprehensive ones. Beyond the delays in implementing the RCCAP due to bureaucracy and lack of funding, Ms. Maknea points out that many Regions and Municipalities treat these tasks as service provisions rather than technical projects. She emphasizes that the Region bears ultimate responsibility for water channel management, and therefore, in the event of a flood, it should be accountable for any mistakes and omissions that may become evident.

A different anti-flood planning approach for Thessaloniki and the Region of Central Macedonia, prioritizing mountain water management works, and prioritizing upstream hydrological works to control flood waves while they are still forming in higher altitudes, is emphasized1 by Professor Yiannis Mylopoulos of the Faculty of Engineering at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTh). Mylopoulos also heads the regional political faction “Change in the Region of Central Macedonia” and is a former dean of AUTh. “It’s not just that the water quantities have significantly increased due to heavy flood runoffs occurring in short time frames; it’s also the overall perception of flood protection. Where we once fortified vulnerable systems, water and runoff channels, we now need to secure the entire hydrological basin from the highlands down to the lowlands,” he points out.

“Water channels in the Region of Central Macedonia (RCM) overall, and in Thessaloniki in particular, are completely unprotected, because the outdated approach of localized projects, which progress slowly, receive minimal funding, and often serve political rather than environmental interests,” notes Mr. Mylopoulos. “In other words, projects are implemented in areas where mayors and stakeholders are favorable to interests of the regional government,” he emphasizes. He further describes the Regional Flood Risk Management Plan (RFRMP) as a vague document that outlines certain principles without providing any specific details.

In the past, there has often been, intentional or not, confusion about who is responsible for cleaning water channels, drains, and sewers to ensure that water volumes can be discharged without flooding streets, shops, and homes. The Thessaloniki Water Supply and Sewerage Company (EYATH S.A.) officially clarified on September 20, 2019, that “the company’s primary responsibility is the operation and maintenance of Thessaloniki’s combined sewer system (which drains both stormwater and wastewater together).” At the same time, it emphasized that “outside EYATH’s jurisdiction, but of critical importance for Thessaloniki’s flood protection is the systematic cleaning of the city’s open water channels, the large closed conduits that the channels drain into, and the cleaning of major roadways.” It further pointed out that these responsibilities largely fall to the regional government and, in some cases, municipalities.

Many scientists and public officials involved in flood protection emphasize the need for soil and green spaces to absorb large volumes of water. In Thessaloniki, such spaces are scarce because for decades cement has been considered more clean and modern than natural soil. Experts recommend breaking up the concrete and replacing it with soil, which can quickly absorb water during critical moments. Undeveloped municipal spaces that are used as car parking areas should be left unpaved, providing a solution for water runoff in the city’s densely built neighborhoods.

In many areas where natural streams once flowed that were later covered, channeled, or buried underground, flood problems persist to this day. A well-known example is Ethnikis Aminis Street, which turns into a river every time there is heavy rainfall, as well as the water runoff through the Exhibition area, which used to pass where the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art now stands. This serves as a testament to the saying that “water remembers” the paths it once took. When it comes in large volumes, no human intervention can stop it—unless there is a radical and immediate response from the regional government and the municipalities. Beyond sporadic cleaning efforts, decisive action must include reopening old water channels, demolishing illegal structures that block water flow to the sea, etc. Only through such decisive actions will Thessaloniki be able to manage flood events like Valencia’s with minimal loss of life and disruption to the city.

Research and editing: Jason Bantios, Stavroula Poulimeni, Tilemachos Fassoulas

Up next: The Troubled Seich Sou: Fire Protection Without Protectors

The research of the independent media cooperative Alterthess titled “Urbal Resilience, Climate Neutrality: The case of Thessaloniki” was realised with the support of Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung-Office in Greece. Read the complete research here.

- The interview with Yannis Mylopoulos took place in June 2024 [↩]