The climate crisis directly threatens our very ability to secure our food. This is evident from the data provided by scientists and from testimonies of producers in the field. At the same time, however, it is precisely the way we produce our food that is one of the main contributors to the problem.

“Agriculture and the climate crisis are locked in a vicious cycle of dependence and mutual destruction. The climate crisis has direct impacts on our food production, while agriculture as practiced today, namely its industrial and intensive model, is what creates and worsens the climate crisis,” says Elena Danali, Greenpeace campaign lead for sustainable agriculture.

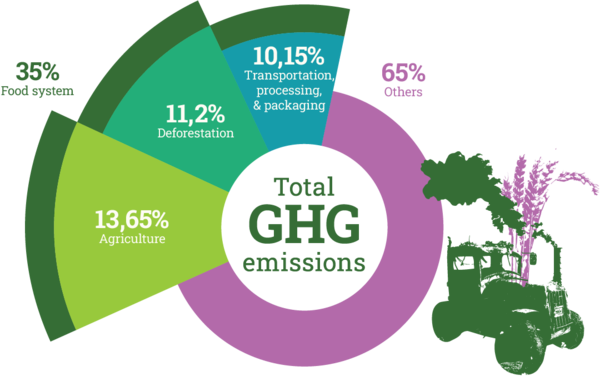

As she explains, the dominant agri-food model relies on monocultures, relies on pesticides and fertilizers, and relies on fossil fuels. “Globally, one third of greenhouse-gas emissions is due to agriculture and livestock,” emphasizes Elena Danali. “Industrial intensive livestock farming alone emits as many pollutants as the entire transport sector combined,” she notes pointedly.

According to the organization GRAIN, the industrial agri-food chain, from field to shelf, including intensive livestock farming as well as deforestation for the expansion of agricultural land, is responsible for 35% of global greenhouse-gas emissions.

The organization underlines that responsibility for this situation should not be sought with farmers, but with the companies that control the agri-food system and drive ever greater industrialization of agricultural production while simultaneously concentrating land and creating oligopolies.

Multinational giants control the agri-food chain, while small-scale farms are being pushed out of the market

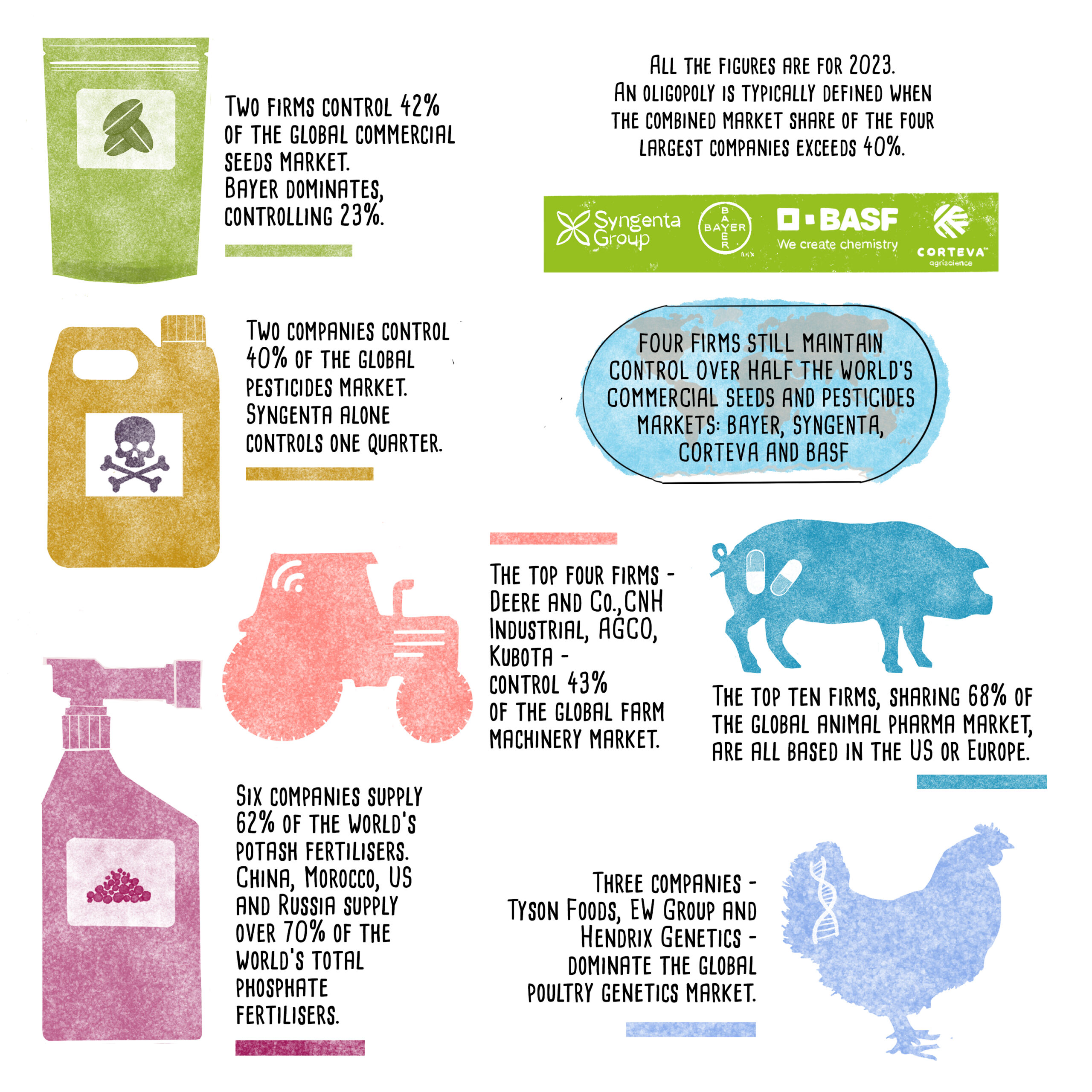

According to the ETC Group’s publication “Food Barons 2022,” in four sectors of the agri-food chain, seeds, pesticides, agricultural machinery, and veterinary pharmaceuticals, we find the very definition of an oligopoly, as four companies control over 40% of the market.

Particularly with regard to seeds, the starting point of the agri-food chain, four companies (Bayer, Corteva, Syngenta, and BASF) control 57% of the market, while Bayer and Corteva alone control 42%. Unsurprisingly, the very same four companies control 61% of the pesticide market; only, in this sector, Syngenta holds the lead, controlling 25% of the market on its own.

“Today, between the world’s 570 million food producers and the 7.2 billion food consumers, there are only four corporate giants that trade agricultural products. These four traders control 75% of agricultural production,” says Elena Danali. “Control of agricultural production runs through every stage. From the seed, which is patented so producers cannot save seed for the next season; through the inputs; through access to markets, distribution, processing, legislation, policy, and financing… Every stage needed for agricultural production to start from the Earth and reach our plate is controlled by a handful of corporate giants and not in the hands of citizens and producers,” she stresses.

In the beginning was the seed

Greenpeace’s report “Industrialize or Quit” presents data on how the existing agri-food system forces farmers to industrialize in order to remain in the profession, pushing many small-scale farmers to cease their activity. According to Eurostat, in 2020 the EU was left with 9.1 million farms, about 5.3 million fewer than in 2005, a 37% decrease in 15 years.

This trend is reversed when it comes to industrial-scale farms, with an economic output above €250,000 per year, which increased by more than half (+56%) between 2007 and 2022. Moreover, the even larger farms, with an economic output exceeding €500,000 per year, almost doubled, increasing by 96%.

The Greenpeace report highlights something else important: Although there are now fewer commercial farms in the EU, they produce more than before, according to the average economic value of their output. Economic output per farm increased in the EU between 2007 and 2022, with larger commercial farms driving this rise by increasing their output by 51%. The pressure on farms to increase their economic performance, often accompanied by more destructive industrial farming practices, also means that economic power in agriculture remains concentrated in the hands of a few farms.

Common Agricultural Policy: In favor of large industrial farms and not of small farmers and the environment

The shrinking of small-scale farms in the EU is exacerbated by inequitable access to financing. “There is a major gap between small-scale farms and large-scale farms, both in terms of public financing, i.e., subsidies from the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), and private financing, which is primarily from banks,” emphasizes Elena Danali. “One percent of the largest farms in the European Union receives one third of European funding,” she notes.

“The first and foremost problem of the Common Agricultural Policy,” Ms. Danali continues, “is that it is area-based: the money goes to hectares, not to crops, not to whether healthy food is being grown or by what methods the farm is kept healthy. This means that whoever can buy or rent land appears as a producer, regardless of what they produce and how. Another great injustice of the CAP is that production of our food is not prioritized. Money goes to livestock, regardless of whether it is intensive, industrial, and polluting, or to the production of biofuels rather than to food production.”

The EU’s Common Agricultural Policy was established in 1962 as a partnership between European society and its agricultural sector. On the one hand, it promised to ensure sufficient, quality food for all European citizens; on the other, fair pay and a decent income for European farmers.

Unfortunately, 60 years on, it is widely acknowledged that the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy, as designed centrally and implemented by member states, has failed in these goals, despite consuming nearly one third of the EU budget. Notably, for the period 2021–2027, the official CAP budget exceeded €385 billion.

At the same time, according to the EU’s own data, farmers’ incomes remain about 40% lower compared to incomes in other sectors, while more than 42 million people in the EU cannot afford a quality meal every other day. That is nearly one in ten EU residents.

The current CAP (2021–2027) was presented by EU leaders as greener and fairer. Aligned with the European Green Deal (Farm to Fork Strategy) and the Biodiversity Strategy, the latest CAP introduced so-called “eco-schemes” to promote environmental practices, such as reducing pesticide use by 50% by 2030, and tied a portion of subsidies to their implementation. Faced with fierce farmer protests, angry demonstrations in many European countries in early 2024 expressing anxiety about incomes and their future, the EU leadership ultimately rolled back significantly, withdrawing, for example, the pesticide provision. In practice, it once again satisfied the interests of agribusiness giants, without offering farmers any meaningful way out.

“Farmers naturally took to the streets over the CAP. But the farmers’ problem isn’t the eco-schemes. It’s how they are supposed to apply them without any support, any assistance, any policy guidance, any safeguards,” Elena Danali tells Alterthess. “The farmers’ problem is not the environment. Nature is not the farmers’ adversary, and biodiversity is not a problem. Biodiversity is a solution. The farmers’ problem is injustice, the gap, political indifference, and exploitation,” she underscores.

More on the directions and outcomes of the Common Agricultural Policy in Alterthess’s podcast “No Farmers No Food: What’s going on with European agricultural policy?”

Jean Thevenot, a farmer from the Basque Country and a representative of Via Campesina in Europe, who spoke to Alterthess, describes European policies to tackle the climate crisis as “almost frightening.” “The European institutions, basically the actors responsible for climate change, are trying to convince us they have the solution. We believe that’s not possible,” he states plainly. “The problem is industrial agriculture. And whatever changes you make, even if you use GMOs or other technologies, the result will be the same, because this model is built on profit. By contrast, the family-based model of food production, which we in Via Campesina defend, is not based on profit. Its goal is to feed people. That is the fundamental difference,” Thevenot emphasizes.

Via Campesina’s representative argues that the European Union is turning increasingly to market-tailored solutions, with no real effect in addressing the climate crisis. He also expresses serious reservations about proposals such as carbon farming or regenerative agriculture as currently promoted by European institutions.

“We fear that the Commission’s proposal on carbon farming, which is based on financial markets and the sale of carbon credits, will attract new actors into the sector, and these new actors will buy land to produce carbon credits instead of food. We’re already seeing this, we have examples within Via Campesina’s network in the United Kingdom, and also from Portugal, where crops are essentially being lost because of carbon farming,” says Jean Thevenot. As for regenerative agriculture, he adds: “On paper it looks very good, but in reality it is being promoted by huge industrial companies like Unilever, Nestlé, and others. It’s just nice ‘greenwashing.’”

In contrast to mainstream policies, Via Campesina, a global movement representing more than 200 million farmers and agricultural workers worldwide, proposes peasant-based agroecology, an agroecology rooted in farmers. “We say ‘agroecology’ because we truly want to work with nature, and ‘peasant-based’ because it should come from farmers for farmers, not be imposed by outside actors,” Jean Thevenot explains. He also reintroduces the term “food sovereignty,” which Via Campesina first put forward in 1996. “We were the first organization to speak of food sovereignty instead of food security. Food security deals only with numbers, and we considered that insufficient. We cannot measure only calories. In our definition of food sovereignty we include concepts such as democracy and citizen participation, so that we can have a food system that is fairer, more equitable, and, above all, locally adapted, meaning that crops suited to each region and its local population are cultivated.”

Asked whether this alternative agroecological model, based on small-scale farms, can in fact feed the Earth’s eight billion people, Jean Thevenot tells Alterthess emphatically: “Clearly yes. It is not industrial agriculture that feeds the planet, it is us, small and medium-sized farmers. Family farming today produces 75% of the food consumed on the planet.” For any skeptics, the Via Campesina representative points to a report published in 2019 by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, on the occasion of the United Nations Decade of Family Farming.

In 15 years, Greece lost 31% of its farms

Within this international and European context, the Greek agricultural sector is also facing critical challenges. It is noted that in Greece, too, the dominant agricultural model, although not large-scale, due to the country’s specific characteristics, remains industrial and relies on intensive, chemical agriculture.

Greek agriculture is marked by key weaknesses such as small farm size, with the average area per agricultural holding in Greece around 50 stremmas (5 hectares), compared to 170 in Europe. Moreover, 52% of Greek holdings cover up to 20 stremmas (2 hectares), which significantly increases production costs for Greek farmers. At the same time, producers’ collective organization, which could offset small, fragmented holdings, is very weak. Notably, the share of products marketed through cooperatives in 2015 was only 20%, while in Europe it is more than double.

The climate crisis, whose harsh face we saw in Greek agriculture with the catastrophic storm Daniel in Thessaly, and which also brings long-term consequences, as we saw, for example, in Central Macedonia, makes a strategic plan for the country’s primary sector even more necessary.

“It’s not only the climate crisis; it simply adds to existing distortions and structural problems, creating a truly perfect storm that truly drives people out of farming every year,” stresses Athanasios Saropoulos, president of the Geotechnical Chamber of Greece (GEOTEE) / Central Macedonia branch.

Greenpeace’s “Industrialize or Quit” report shows that the same trend toward concentration in large farms is recorded in Greece, as in the rest of the European Union.

Specifically, between 2007 and 2021, Greece lost 31% of its farms. This reduction concerns exclusively small-scale farms, which shrank by 37%.

Also listen to / Lois Lambrinidis: Climate policies cannot be implemented without farmers

At the same time, although Greece still has only a few industrial-scale farms (with economic output above €250,000), their number has clearly increased, from 540 to 860 farms (+59%). Among these industrial-scale farms, there were only 40 with economic output above €500,000 per year in 2007, whereas by 2021 there were already 300.

Structural problems and the absence of a national strategy

Speaking to Alterthess, Athanasios Saropoulos highlights the absence of a national strategy for the agricultural sector since the early 1980s. “We relied on European subsidies and, in some cases, we ended up corrupting farmers, having them not produce, just collect,” he stresses. He notes that even after the economic crisis, producers’ efforts to turn to quality products and exports were not supported by a coherent government policy, neither at national nor at regional level.

The consequences of this lack of strategic planning are now visible in terms of food self-sufficiency. “Greece is not self-sufficient in basic foodstuffs. If, for any geopolitical reason, imports were interrupted, as we already saw with the war in Ukraine, then we would face enormous problems,” warns Mr. Saropoulos.

According to the figures he cites to Alterthess, only 25% of beef and pork is produced domestically; the country imports 70% of its soft wheat, used to make bread, while the production of potatoes, milk, and pulses is insufficient to meet internal needs.

“If imports were to stop, the Greek family would have to reduce its diet by two-thirds or more,” Mr. Saropoulos notes emphatically. He also stresses that the Common Agricultural Policy played a role in leading the country into this state of dependence on imports.

“For example, the EU subsidy for durum wheat was intended to favor the Italians, who had the pasta industry. What did we do in Greece? Back in 1981 we had 7 million stremmas of soft wheat and 2 million of durum. Because of that subsidy, it became 7 million stremmas of durum wheat, and, in fact, many of those fields didn’t even produce; they were declared just to collect the subsidy, and only 2 million stremmas of soft wheat remained. This change happened within two decades, from 1982 to 2001. The subsidy created the problem; it is a measure decided by the European Union,” Mr. Saropoulos emphasizes.

.

While strongly criticizing EU leadership for the directions of the Common Agricultural Policy, Christos Tsantilas, agronomist-soil scientist and former director of the Hellenic Agricultural Organization DIMITRA’s Institute of Industrial and Forage Crops, is also keen to point out the responsibilities of Greek governments. He offers a telling example, this time from cotton cultivation, to show how Greek governments, from very early on, failed to use EU funds within an integrated plan.

As Mr. Tsantilas tells Alterthess, the European Union grants Greece around €190 million annually to support cotton production, with the logic, he notes, of strengthening cotton cultivation where it actually takes place, to achieve better yields. “What happened, though? We spread cotton cultivation across the entire country, regardless of where conditions are best for cotton, with the logic of distributing subsidies for micropolitical reasons to all regions. Every local politician in his area could hand out money,” Mr. Tsantilas stresses. As a result, large sums were allocated to cotton cultivation even in areas that are not productive for this crop. Mr. Tsantilas notes, for example, that in Central and Western Macedonia yields reach only 120 kilos of cotton per stremma, while in Thessaly they exceed 400 kilos per stremma. “We cannot cultivate cotton here and there; we must cultivate it where it yields most,” he underlines, calling for an immediate correction of the policy applied to financial support for crops.

It should be noted that when Mr. Tsantilas pointed out this need to us, the OPEKEPE scandal had not yet even come to light…

More in Alterthess’s podcast “CAP in Greece: Subsidies, distortions, and scandals”

Farmers without state guidance in the face of the climate crisis

The climate crisis framatically brings to the forefrontthe chronic distortions and weaknesses that characterize the development of Greece’s agricultural sector and makes a strategic plan from the State imperative, with the aim of shielding Greek agricultural production, shifting toward more environmentally friendly practices, and truly supporting farmers.

Christos Tsantilas proposes establishing agroecological zones, in order to match crops to the regions where they can yield more and better. “We need to put the producer in a position to cultivate what will bring the greatest possible benefit, not have them cultivate any crop anywhere just so we can give a subsidy as a small aid. If agroecological zones are created, each region will know what crop it should plant, and there we can indeed provide financial support for that cultivation,” he notes.

For his part, Mr. Saropoulos underscores, among other things, the need for scientific guidance to farmers so they can cope with the impacts of the climate crisis in their fields. “In the past, there was an agronomist at the local agricultural economics office who had a demonstration plot and conducted trial cultivations. That is, they would show a new cultivation method; everyone in the area would see it, and some, the more pioneering and younger ones, would follow. That structure was abolished,” he says, adding: “Our proposal as a chamber is that so-called agricultural extension services be re-established in every prefecture’s agricultural economy and veterinary directorate, with a specific mandate: adaptation to the climate crisis.”

It is noted that GEOTEE Central Macedonia has submitted a comprehensive memorandum to the Prime Minister and all relevant bodies, with the branch’s proposals for addressing climate change in the primary sector and the natural environment of Central Macedonia.

“We must realize that we need very big changes. Let even the last person understand that the issue of the climate crisis is not a slogan. The disasters in Thessaly reminded us, in the harshest way, of what scientists were warning us about,” stresses Lois Lambrinidis, economic geographer and former professor at the University of Macedonia.

He calls for the trauma of Thessaly to serve as a turning point for policies that “take us elsewhere,” as he puts it. “These policies cannot be at the level of the individual farmer. The individual farmer cannot solve this issue. It requires collectivity; it requires a state that creates institutions; it requires science to stand alongside. It requires a different development model. That has not happened in any way,” says Mr. Lambrinidis.

“Producers are victims of the climate crisis,” emphasizes Elena Danali. “Both because they experience its impacts and because they are abandoned when it comes to implementing the other agricultural model we are discussing. Producers need three things: financing, know-how, and access to markets. All three cannot be left on their shoulders. They are the responsibility of the State,” she explains, adding: “When there are no policy decisions and measures that favor an agricultural model that halts the worsening of the climate crisis, there is ample room for exploitation, monopoly, buy-outs, profiteering, and injustice, and, ultimately, this vicious cycle of dependence and mutual destruction (climate and agriculture) intensifies.”

Alterthess approached the Ministry of Rural Development and Food to discuss the challenges of Greek agriculture against the backdrop of the climate crisis and the government’s plan to address them. Despite our persistent request for an interview with Minister Kostas Tsiaras, we had received no response by the time this investigation was published.

Uncontrolled occupation of agricultural land by solar panels

At a time when the climate crisis is putting pressure on Greek agriculture, bringing even food sufficiency issues to the fore, one of the supposed solutions to tackle it is creating even greater problems: the development of industrial-scale photovoltaic parks, which have been expanding rapidly since 2020, occupying vast tracts of agricultural land.

The gigantic 246 MW photovoltaic park planned over 4,500 stremmas in the Municipality of Nea Chalkidona in Central Macedonia, in an area with vineyards and cereal crops, is just one telling example.

Up to 320,000 stremmas of high-productivity agricultural land can be covered by photovoltaics across Greece, according to the legal provision (Law 4711/2020), while no limit is set for the occupation of ordinary arable land.

“Changing the land use of high-productivity agricultural land is unconstitutional,” declares Athanasios Saropoulos, president of GEOTEE Central Macedonia, speaking to Alterthess. As he explains, “there is a prior Council of State decision stating that protection of high-productivity land is protection of a scarce natural resource and thus falls under Article 24 of the Constitution, which protects forests.” Mr. Saropoulos believes that, in the end, the protection of agricultural land can only be achieved through appeals to the Council of State and judicial rulings.

He characterizes the installation of photovoltaics on irrigable land as a crime and an absurdity. “Consider this: in the Thessaloniki plain, we’ve been building irrigation networks since the 1960s; canals run from the rivers to water the fields. And right there they plonk a photovoltaic installation because, theoretically, it is permitted.”

Mr. Saropoulos also denounces the practice of so-called “salami-slicing” of projects by companies in order to game the system and obtain permits. “There are very large projects that received approvals piece by piece. Agencies could not see that, say, a single sheet of glass covering 5,000 stremmas would be installed, because they ‘cleverly’ got licenses for 100 stremmas here, 100 there, and ultimately some large companies stitched them together and want to create unified photovoltaic parks, the largest in Europe, on the order of thousands of stremmas,” he explains.

As president of GEOTEE / Central Macedonia branch, Mr. Saropoulos has raised these issues in a letter to the Ministry of Rural Development and Food as far back as 2021, stressing the need for proper spatial planning so that the development of renewables does not compete with other natural resources and agricultural production.

“There are many millions of stremmas in Greece that are completely non-productive, many areas that are rocky. Renewable energy units could be installed there, so you don’t lose agricultural land,” stresses Christos Tsantilas. “Of course, that would mean the energy companies would gain less financially, because they would have to undertake more expensive projects, as they would be much further from the grids,” he adds meaningfully.

In 2022, Mr. Tsantilas published the study “Solar Energy & Agriculture: An Inseparable Dynamic Relationship” as a scientific associate of the Institute for Alternative Policies (ENA). In it, as does Mr. Saropoulos, he underlined the need for sound spatial planning and a comprehensive policy so that photovoltaics could even help the agricultural sector by providing solutions to farmers for dealing with high energy costs. However, as he tells Alterthess, “legislation on renewables and photovoltaics is made to order for the large energy companies, utterly disregarding the destruction of agricultural land. This means a reduction in agricultural products. This means a major problem for the rural population.”

Mr. Tsantilas also points to the issue of transparency regarding how much high-productivity land has already been taken. “HEDNO, which has the data, has not provided it despite repeated requests, from researchers, from agencies, even from politicians who requested it to submit questions in Parliament. Because there is a policy of covering up in this area,” notes Mr. Tsantilas.

It should be noted that HEDNO and IPTO are the competent authorities to check whether the cap on installing photovoltaic parks on high-productivity agricultural land has been reached in each regional unit and, by law, they must publish the relevant data on their websites every two months. Nevertheless, they did not disclose this data even when farmers requested it by extrajudicial notice, threatening to seek injunctive relief.

Mr. Tsantilas notes that the uncontrolled installation of industrial-scale photovoltaics not only reduces agricultural production but also diminishes its overall quality and distinctive value.

He adds that, according to international studies, in the case of industrial-scale photovoltaic parks exceeding 300–400 MW, the average temperature in the surrounding area increases, over quite a large expanse, by up to 4°C. “For example, in Thessaly in summer the temperature can reach 42°C. If in some area the temperature rises further due to photovoltaics, even the lives of people in neighboring villages will be at risk. Beyond the fact that nothing will remain of the crops, because a literal furnace will be created,” he says.

Mr. Tsantilas emphasizes to Alterthess that the development of large industrial parks ultimately has the opposite effect in addressing the climate crisis, since in the soils left uncultivated to host photovoltaics, the functions related to carbon dioxide absorption will cease. “Instead of that, we will end up producing more heat,” he stresses.

“And consider this: if at least the energy produced were used by farmers for their own needs, to pay their electricity, to pay for diesel, one might say, fine, let’s do it, because we are strengthening agricultural production. But the energy produced by these units is energy generated by large companies that sell it on the power exchange. The quantities produced are so large that they are often lost on the grid; we don’t even want them. Yet we produce them after having destroyed agricultural land,” Mr. Tsantilas concludes.

Up next: In the Beginning Was the Seed

The research “The Climate was already bad” was realised with the support of Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung-Office in Greece. Read the complete research here.