The climate crisis is no longer a distant scenario of the future. It is here, and it is already leaving a strong imprint. The data are unforgiving: temperature is rising, extreme weather events occur more frequently, and the natural environment is being tested. Alongside it, agricultural production is also being tested, as those who work the land know all too well.

Watch the video: Agriculture at Risk

The catastrophe in Thessaly, the country’s agricultural capital, after Storm Daniel in September 2023 is a traumatic reminder. However, the consequences are also painful due to the gradual change in the climatic parameters on which agriculture depends, such as rainfall, drought, and temperature. “This gradual change is occurring in a way that does not attract interest or the spotlight; it is as if we do not see that it is happening, yet it is happening and it radically affects agricultural production,” emphasizes Elena Danali, Greenpeace’s sustainable agriculture campaign coordinator. She also underlines that the systematic study of climatic parameters is necessary as the basis for the decisions and measures the government needs to take, both to stem the worsening of the climate crisis and to restructure the agricultural sector.

Along with the field research it carried out, speaking with producers in Central Macedonia about the effects of the climate crisis they are already observing in their fields, Alterthess met with the scientists most qualified to speak about the new climatic data and how it affects agriculture, either directly or in the longer term.

Rising temperatures and torrential rain

Kostas Lagouvardos is Director of Research at the National Observatory of Athens. He also coordinated a team of scientists commissioned by Greenpeace to study changes in Greece’s climatic parameters over the last 30 years. The results of this study were presented in March 2025 in the report “Climate and Agriculture in Interlinked Crisis.”

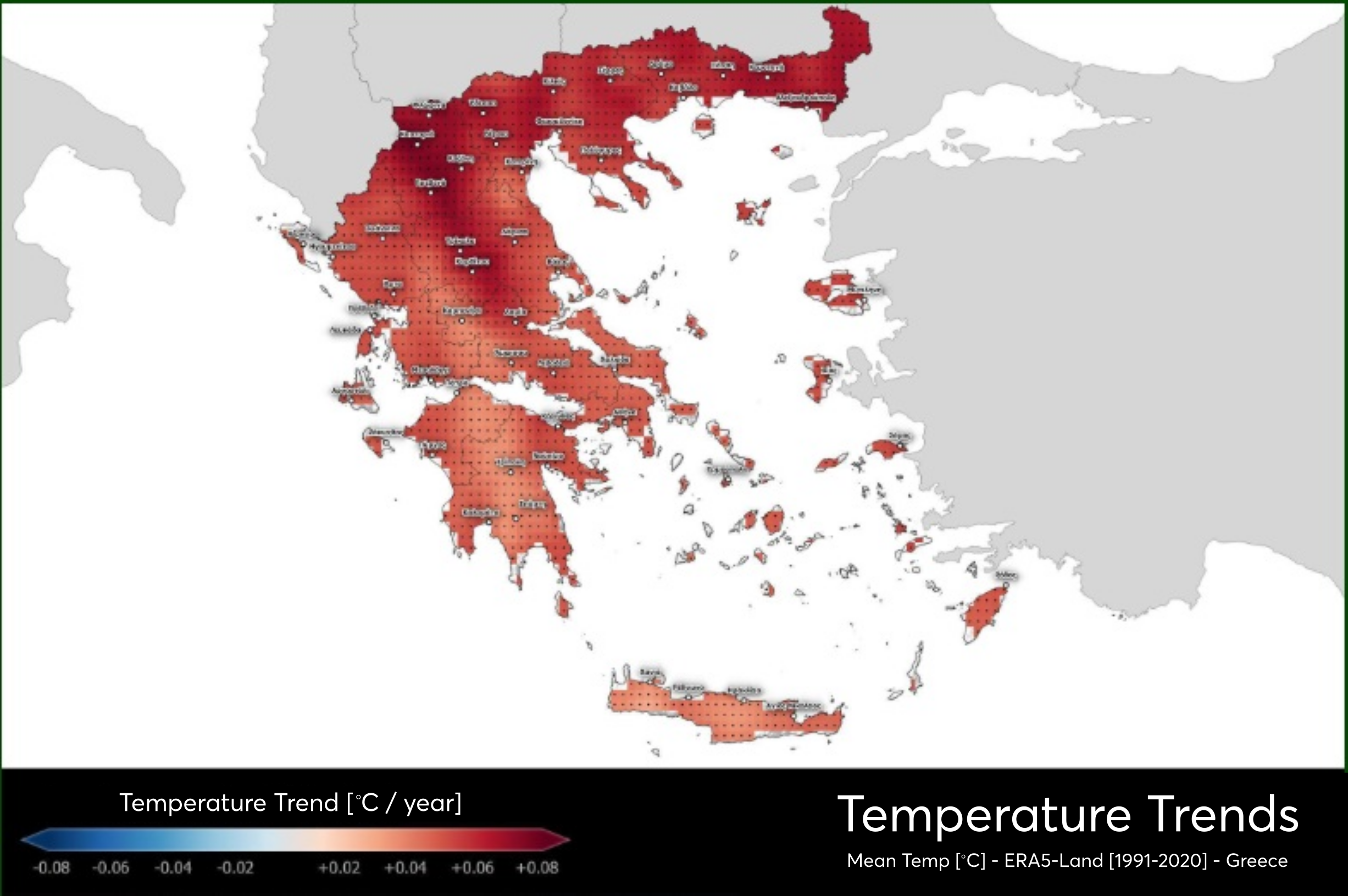

Alterthess met with Mr. Lagouvardos, who informed us about changes in critical climatic parameters, beginning with temperature. “According to the data we have from all sources, over the last 30 years the average temperature in Greece has increased by about 1.5°C,” Mr. Lagouvardos notes. As he stresses, “this is a very significant increase because thirty years is a relatively short period.” The increase is not uniform across the country. Regions such as Central and Western Macedonia have recorded a thermal rise exceeding 2°C. In contrast, areas such as Crete or the Aegean islands show a smaller increase due to their proximity to the sea. “This does not mean that it is hotter in Central Macedonia than it is in Crete. However, the rate of temperature increase in northern Greece is faster than in the south,” Mr. Lagouvardos clarifies.

The rise in temperature concerns not only the land but also the sea, with northern areas warming more rapidly once again. “In the Thermaic Gulf, temperatures approached 30 degrees during the major heatwaves we had in ’21 and ’23,” Mr. Lagouvardos reports, adding that these “marine heatwaves” burden marine ecosystems as well as crops connected to our agri-food sector, such as mussel farming in the Thermaic Gulf.

“In general, long-lasting heatwaves are becoming more frequent, especially over the last ten years. A heatwave is a very dangerous weather phenomenon, insidious, as we say among ourselves. Even though it does not create the commotion of a storm or a downpour, it ultimately kills and affects more people and puts enormous strain on the agricultural sector,” Mr. Lagouvardos tells us. In 2023 the country recorded its longest heatwave, with 15 consecutive days. The record was surpassed the very next year, in 2024, with 16 days.

The rise in temperature is, of course, only one of the parameters that show how climate change manifests. Changes in the intensity of rainfall or in snowfall have significant negative effects on the hydrological cycle.

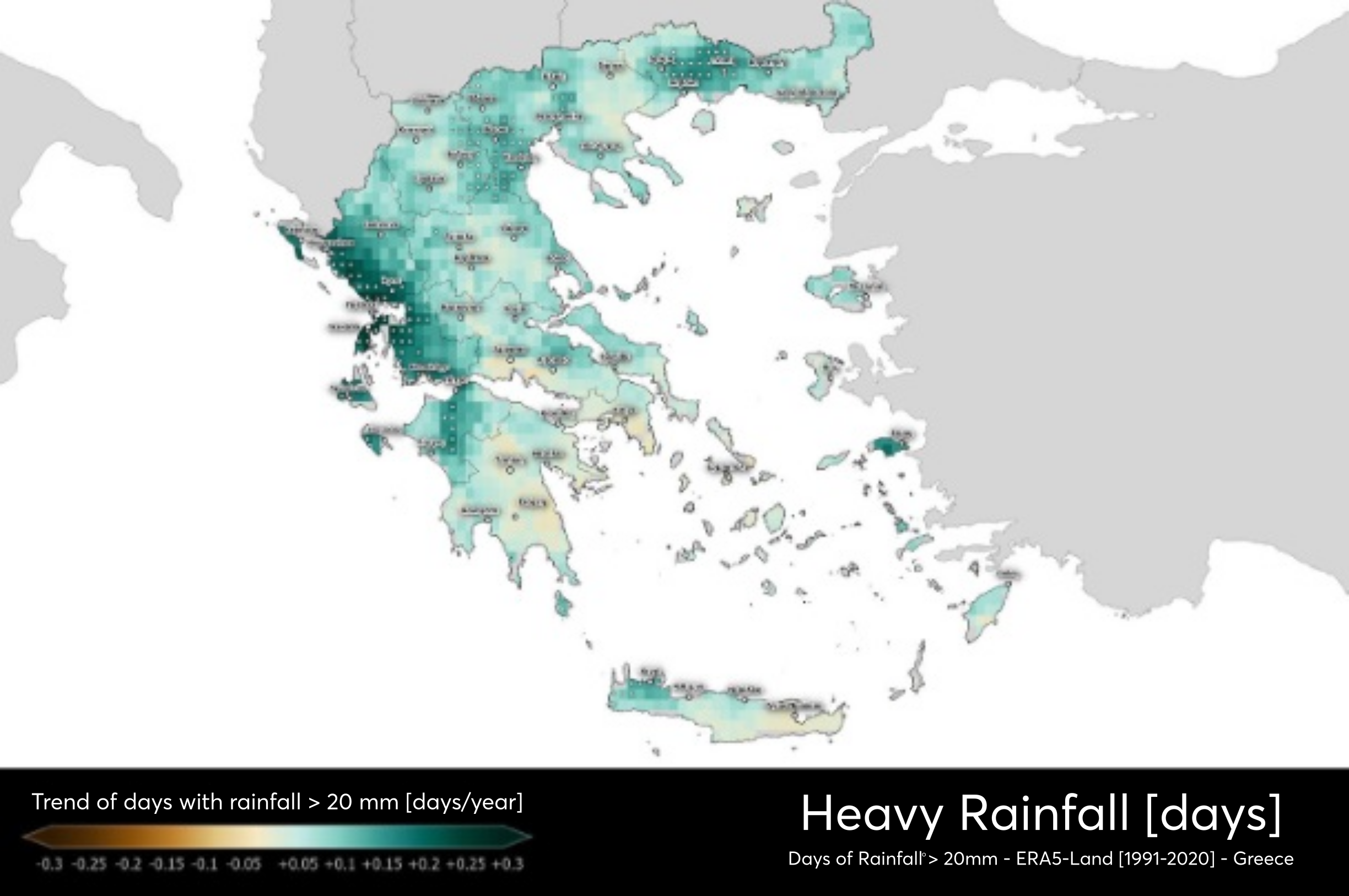

Mr. Lagouvardos explains that, over a thirty-year period, rainfall totals have not changed significantly; they are more or less the same, with some good and some bad years. What has been observed, however, is a qualitative difference, as torrential downpours are now more frequent. “As you can understand, this creates a major issue, because on the one hand a torrential downpour causes destruction, and on the other hand, in a torrential event we may measure that a great many millimetres of rain fell, but the water does not have time to be absorbed; it runs off in torrents to the sea and is lost. We obviously prefer slower, soaking rains,” Mr. Lagouvardos stresses.

The reduction in snow is also an indication of thermal change. There has been a significant decline both in snow depth and in the number of snow-cover days on the mainland. This affects the hydrological cycle, since snowmelt is vital for the gradual replenishment of groundwater. “Less snow also means fewer water reserves at the end of the day,” Mr. Lagouvardos notes.

“The other aspect,” he continues, “is drought. We saw this, for example, in Thessaly. In September ’23 we had major floods with enormous rainfall totals, and by October ’24 a severe drought; October ’24 was a very dry month across the country, even though it is an autumnal month, people could not plough because the fields were completely parched by the drought.”

Overall, in 2024 most regions of Greece experienced an increase in the number of dry days compared with the 1991-2020 average, according to the climate assessment for Greece in 2024, as recorded and presented by the scientific team Climatebook, of which Mr. Lagouvardos is also a member.

Thessaly as a climate victim: Desertification risk after the disaster

Another parameter of the climate crisis concerns extreme weather events. Kostas Lagouvardos notes that they have always existed and that we cannot attribute everything intense that happens to climate change. “Sometimes it is used as an alibi,” he stresses.

He adds, however, that climate change has not created extreme weather phenomena, but has made them appear more often and become more intense, thus causing greater destruction. “At the Observatory we systematically record severe weather events in our country and we see an increase from one decade to the next. Looking at the last 20 years, we have roughly a 50% increase in the frequency of very strong weather events. They are becoming stronger and therefore more destructive,” Mr. Lagouvardos reports.

“The climate crisis contributed to the intensity of the phenomenon that affected Thessaly,” Mr. Lagouvardos notes characteristically. As he explains to Alterthess, both Storm Daniel in early September ’23 and Elias in late September ’23 were systems that would have occurred regardless. However, scientists found that the very warm sea, due to the very high temperatures in the summer of ’23, contributed to producing more rain-bearing systems. “Why did this happen? Because when the sea surface warms, evaporation increases, more, faster, and more easily, the surface water turns into water vapour, that vapour feeds the clouds, and these in turn give rain. Therefore, the systems that affected Thessaly would have existed in any case; they simply became more intense and more rain-laden, which is why we had intense rainfall totals, also due to the very warm sea.”

The direct consequences of such a disaster are, of course, immediately perceptible. In Thessaly, 17 people lost their lives within the first 24 hours after Daniel. More than 1 million stremmas were flooded, 25,000 farmers saw their fields destroyed, while more than 110,000 animals and 135,000 birds were lost.

There are, however, long-term consequences with disastrous results for agriculture. Agronomist and soil scientist Christos Tsantilas, former director of the Institute of Industrial and Livestock Crops at ELGO Dimitra, explains, for example, the effects of extreme rainfall on the soil on which agricultural production depends.

In sloping areas, Mr. Tsantilas clarifies, soil erosion occurs. “When water falls with great intensity and large volumes move at high speed, it carries away enormous quantities of soil. This means that the fertile topsoil is removed, the subsoil remains, which is barren, and many times we reach the so-called base rock. All the soil goes.” To understand what this means, he invites us to consider that it takes 500 to 1,000 years to form one centimetre of fertile soil on base rock, while with a single extreme downpour one or two metres of soil can be lost within two or three days. “We can therefore understand the damage done to natural processes; the destruction is immense. These areas are now barren and, if very serious measures are not taken—which are difficult to implement and economically burdensome, they will become desertified,” Mr. Tsantilas underscores.

Despite scientists’ persistent requests, in Thessaly no state survey was carried out concerning soil loss after Daniel. Mr. Tsantilas, who traversed the entire region, has the impression that “all the hilly areas of Thessaly, and there are many, have been affected to such a degree that one could say they cannot be cultivated again.” Among these are very fertile areas in terms of the production of basic agricultural products, such as cereals. “For example, the area from Larissa to Farsala, which is hilly and had a large output of durum wheat, we do not know whether it will be cultivable again,” Mr. Tsantilas notes.

In the flat areas that were covered with water for months, or even for more than a year, such as around Lake Karla, destruction came in another way. “There the soils died; whatever biodiversity existed in the soil was lost.” Mr. Tsantilas explains: “Soil is not a sum of simple materials; it is a vast biochemical laboratory. In a handful of soil there are billions of micro-organisms and macro-organisms. One quarter of the planet’s organisms, large and small, exist within the soil, even though we do not see them. All this biological activity died, as organisms submerged under water no longer had oxygen.”

“The issue is that, in order for soils to become productive again after the waters recede, it is not enough simply for them to dry out; this soil biodiversity, these micro-organisms, must be recreated, and they do not arise from one day to the next, they need time,” Mr. Tsantilas notes.

Shift in cultivation zones: Central Macedonia as a hot spot

Even if extreme weather events with their destructive consequences draw public attention and provoke some state response, there are other impacts, equally serious for our food production, which escape notice.

“The fundamental impact of the climate crisis on agriculture is that cultivation zones are changing, in other words, the types of crops that can thrive in each area,” Elena Danali, Greenpeace’s sustainable agriculture campaign coordinator, tells Alterthess.

In Greenpeace’s report “Climate and Agriculture in Interlinked Crisis,” we read that the first effects of these changes are already evident. In 2024, in several regions of the country, high spring temperatures combined with drought affected both the quality and quantity of annual crops (cereals, pulses).

For annual crops (e.g. cereals, vegetables, pulses), this may mean a gradual shift of cultivation zones further north, something that could lead to the economic and social ruin of entire regions that have cultivated them for centuries. For existing tree crops (olive, vine, stone fruits, pome fruits, etc.), such a scenario would also be disastrous, since they cannot be moved. The first effects have already appeared, as mild winters have brought a reduction in differentiated buds that produce flowers and subsequently fruit.

Christos Tsantilas, agronomist and soil scientist and former Director at the Institute of Industrial and Livestock Crops of ELGO Dimitra, explains in more detail how climate change affects plants: “The following happens: not all plants have the same thermal needs; they have various peculiarities in this regard. For example, in order for certain plants to be able to produce flowers and then fruit in the next season, they need in winter a fairly long period of low temperatures, around zero or often below zero. If winter temperatures are not low, as has been the case recently, the number of cold days required for plants to form flowers and fruit in the following period is not accumulated, and the result is an automatic reduction in plant production.”

It is mainly tree crops that face this problem. “For example, we have seen this phenomenon in recent years in olive production, where yield has decreased because winters were warm and the chill days needed by the crop were not accumulated,” Mr. Tsantilas notes.

Central Macedonia is one of the areas in Greece most threatened by a shift in cultivation zones. Eighty percent of the country’s deciduous fruit trees are grown in its soil, such as peaches, nectarines, apricots, cherries, and other tree crops, which thrived in the region thanks to its transitional climate, ensuring the chill days these plants need to bear fruit. “With climate change, these crops that could not be cultivated further south because it was not cold enough will no longer thrive here. As Central Macedonia warms, production will be taken over by northern countries; it will leave Greece,” emphasizes Athanasios Saropoulos, president of the Geotechnical Chamber of Greece (GEOTEE) for Central Macedonia, stressing the need for comprehensive planning by the state.

The medium, or long-term effects on agriculture from the gradual change in climatic parameters are not limited to the shifting of cultivation zones.

“There are also impacts on cultivation practices, such as irrigation or disease management; there may also be impacts on the development of crops and plants and on their yields. In other words, there are effects at all stages and aspects of cultivation,” notes Elena Danali.

Professor Katerina Karamanoli, Professor of Plant Physiology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, points out further reasons for concern in her comments to Alterthess. “For example, many micro-organisms, plant pathogens and phytophagous insects, have more life cycles within the year precisely because temperatures are higher, or they may spread over larger areas and thus pose problems for cultivation. We may also have issues of synchrony: pollinators and flowering, which, as you understand, need to match up, may fail to coordinate due to temperature, humidity, or other environmental conditions. All these issues affect agricultural production,” Professor Karamanoli emphasizes.

Food security concerns are looming

Scientists once again sound the alarm about the trajectory of climate change. “When we are currently observing an increase of 1.5 or 2°C in some areas, the projections for the coming decades are much more disheartening. We may see a 3 or 4 degree increase in temperature, which will be catastrophic. If we do not take drastic measures quickly, we will face even more significant problems in the future,” stresses Kostas Lagouvardos, Director of Research at the National Observatory of Athens.

For her part, Professor Karamanoli notes that, due to the effects of the climate crisis, issues of food adequacy are now arising. One way we can already grasp the problem is by observing the higher prices of products on the shelf. “We already faced, two years ago, the major reduction in production in Thessaly due to the floods then, during Storm Daniel. In the same year we had olive production decrease and we remember well the increase in the price of olive oil in that period. Last year we had a major reduction in honey production, especially on the islands of the eastern Aegean. These are some examples of reduced production and thus reduced product availability, which may be even greater in the future,” Professor Karamanoli notes.

According to Eurostat data, agricultural production in Greece in 2023 decreased by 16%, a negative first place by a wide margin among all EU member states.

“Research and projections indicate that by 2050 we will have reduced production in basic foodstuffs,” continues Katerina Karamanoli. “For corn, a reduction on the order of 25% is expected. Reduced production is also expected for rice and potatoes, while cereals are expected to shift further north; thus we will see localized reductions in production and possibly food insufficiency among specific populations,” she notes.

Science now has abundant data to monitor and analyze climatic changes. The major challenge, as Mr. Lagouvardos points out, is “to use the data correctly so that we draw the right conclusions and make the right decisions.”

“The climate crisis puts at risk our ability to feed ourselves. At the same time, it strikes the productive fabric of the country, which, of course, has direct consequences for the social fabric,” notes Elena Danali.

For his part, Christos Tsantilas emphasizes: “Climate change affects the heart of human needs, our food. And if we reach that situation, the problems will be uncontrollable.”

Up next: The climate crisis in the field, Farmers have been reading the signs for years

The research “The Climate was already bad” was realised with the support of Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung-Office in Greece. Read the complete research here.