The summer of 2021, beyond the grim news of the pandemic, brought another growing “illness” to the fore: the climate crisis. The news came from Northern Greece and the mussel farms, as the warming of the waters in the Thermaic Gulf destroyed half of the mussel production as well as the spat, that is, the following year’s production. Mussel farmers then witnessed something that in the following years would become more clearly visible in other sectors as well: climate change entering their lives and their farms. “We are the first to have experienced the consequences of climate change,” said Kostas Vervitis, then president of the shellfish fishers’ association “Poseidon” of the Municipality of Delta, the area where 90% of the country’s mussels are cultivated. Unfortunately, since that year things have not improved, and the solutions being proposed remain in their infancy, with mussel farmers often feeling abandoned.

“Mussel farming in the Thermaic Gulf, and in Greece in general, began about 40 to 50 years ago, tentatively in the 1980s and especially in the 1990s. In the mid-2000s it reached its zenith, creating a solid form of primary production and also decentralization, because it concerns the Region of Central Macedonia (Kymina, Malgara, Chalastra, Kleidi of Imathia, and Kitros of Pieria). There are also a few units in Strymonikos, between Halkidiki and Kavala, but most of the production relates to the areas of the Thermaic Gulf,” says Ioannis Giantsis, Assistant Professor in the Fisheries Laboratory of the Department of Agriculture at AUTh, speaking to Alterthess.

Adding up the disasters

In Kymina, on one of the mussel farmers’ boats, K. Vervitis was waiting for us. We traversed a vast expanse of rice fields before reaching the mouths of the Axios River, in a landscape striking in its morphology. May marks the start of the farming season, when mussel farmers place the mussels into the “crystals,” awaiting the completion of their growth process in the summer. Mr. Vervitis was not optimistic, and how could he be, when adding up successive disasters?

“We are starting after a huge disaster last year, the summer of 2024, which resulted in the death of all the spat, as well as a portion of the market-ready mussels. Farmers are currently in dire straits because no compensation has been given by the state, nor any assistance, and everyone is trying on their own to cope with all the damage they have suffered in recent years,” says K. Vervitis, emphasizing how closely tied mussel farming is to the place. In Kymina alone there were 60 units using the longline system, and in earlier times it was the main occupation for many families. In Central Macedonia, active units were estimated at 200, most of them family businesses. Over time, and due to the problems that have arisen, many are abandoning the profession. “Producers have no mussels to sell, families have been left without work, with the result that the workers they employed have gone an entire winter without jobs,” Mr. Vervitis explains, showing us the boats now empty of mussel farmers.

Watch the video: Why are the mussels dying in the Thermaic Gulf?

Mussels are a key export product, and Greece ranks fourth in annual production volumes. During the Covid period, due also to the pandemic’s effects on economic activity, the first blow came for mussel farmers, who failed to export early; as a result, the high temperatures that developed in the Thermaic Gulf led for the first time to mass mortality. The same occurred in subsequent years, culminating in the summer of 2024, when, due to sudden marine heatwaves, mortality rates reached the largest share of production.

Marine heatwaves are killing mussels

How mussel farming works is explained in more detail by Ioannis Giantsis, who delves a bit deeper into the problem. “On the barrels we usually see floating at sea, the longline system is formed, that is, the long-line system where mussels live throughout their lives, from the moment they are collected until they reach commercial size. They feed as filter feeders, filtering seawater and retaining phytoplankton, zooplankton, dissolved organic matter, and any other small organism. Thus, they select waters rich in organic matter, as is the case at the mouth of the Axios, where the four rivers that discharge there bring organic material with them.” As he continues, mussel farming has zero feeding costs since mussels feed from the seawater; it does not constitute a form of environmental pollution because they live in their natural environment; it does not require land use, as they are in the sea anyway. Naturally, they are sensitive to pollution, since they retain whatever is in the water.

“In contrast to wild mussel populations, which live near the sea surface on rocks, etc., and have the advantage of being exposed to air due to the phenomenon of low tide and the shoreline, farmed mussels face high temperatures 24 hours a day,” the professor notes, stating that in the summer of 2024 temperatures above 30°C were recorded at about 1.5 meters below the surface for roughly ten days. These are temperatures far above mussels’ tolerance, which according to the literature extends up to 27°C. “The thermal and oxidative stress created in mussels also causes the mortality phenomena,” he adds. The imprint of this condition on production is enormous: twenty years ago it approached 40 thousand tons, and today it may be limited to 20–25 thousand tons. In fact, some mussel-farming units are estimated to have lost their entire production.

The climate crisis has turned the Thermaic Gulf into a hot spot

Aristotle University (Laboratory of Marine Engineering and Marine Works – AUTh) as well as agencies like HCMR have been studying the state of the Thermaic Gulf since the 1980s. Human activities in the coastal zone of the gulf (industrial activity, agriculture, animal husbandry, wastewater), combined with climate change, have gradually increased the pressures on the gulf.

In their latest research, G. Krestenitis, G. Androulidakis, Ch. Makris, K. Kompiadou, and others identified a dramatic rise in temperature over the last 50 years that has had significant impacts on marine species and aquaculture.

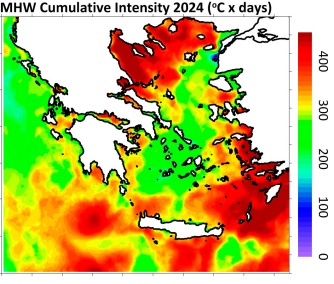

Giannis Androulidakis, now Associate Professor in the Department of Oceanography and Marine Sciences at the University of the Aegean, describes the situation as follows: “The main way we monitor the situation is by observing the thermal changes in the water of the Thermaic Gulf. An increase of around half a degree per decade has been observed for the gulf area, which is slightly above the Mediterranean average. This increase in temperature, which is not limited to the sea surface but can be found throughout the depth of the water column, affects the entire ecosystem and the organisms that are more sensitive to such changes and temperature levels.” According to Androulidakis, in the last 34 years temperatures above 30°C have been detected. These so-called marine heatwaves are both more frequent and longer in duration than they may have been in the past. Thus, if one combines, as he says, the dimension of the climate crisis at sea with human activity, which can cause phenomena such as eutrophication due to fertilizers and pesticides, one understands why the situation is getting progressively worse. “What we have observed is that the increase in temperature and the frequency of marine heatwaves in the Thermaic Gulf is more intense than in other areas of the Aegean and, in that sense, we can define it as a hot spot. Beyond that, this concept is linked to the impacts on mussel farmers, which we know are among the most important cultivations in the gulf.”

In the diagram we see the intensity of the sea heatwaves January-August 2024 which includes the temperature and their duration (Source: Journal of Marine Science and Engineering)

The university has sounded the alarm, but there are no ears to hear it

Can the situation be reversed? It is obvious that dealing with the climate crisis depends on strategies that must be followed at a global level. However, systematic monitoring of the various factors and parameters relating to the phenomenon in the Thermaic Gulf is something that would help in decision-making and the implementation of different policies. Nevertheless, as the report shows and as G. Androulidakis confirms, there has been neither systematic monitoring of the Thermaic Gulf in recent years, nor even a body that could oversee its problems holistically in order to propose appropriate solutions. “You can understand that an unhealthy sea affects almost all organisms and the entire ecosystem, which in turn impacts not only the region economically, as we see with the example of mussel farming, but also other sectors of human activity (public health, tourism).” In this case as well, state intervention comes long after the problem appears and, as he also stresses, is not tied to preventive policies. “Providing compensation to mussel farmers is important, but it is not enough to solve the problem when you neither know nor care to learn in a more holistic way what is happening, and to use research and data to chart specific policies,” he emphasizes. The problems brought by the climate crisis to mussel farming are a central subject of study at AUTh’s Fisheries Laboratory. Scientists, together with mussel farmers, are seeking solutions, trying to reverse, even partially, the bleak situation that has developed. Some of the solutions being investigated are the transfer of mussel units to areas with lower temperatures (Thrace, Central Greece, Epirus). However, a wholesale removal of mussel farming from the organically rich area of the Axios is not considered advisable, since, as Mr. Giantsis points out, “even if we had lower mortality, ultimately we would have lower production.”

Thus, one of the research programs underway focuses on methods to prevent production loss. “With the help of sensors and monitoring of water conditions (oxygen, temperature, pH, chlorophyll), we are attempting to create a system that links mussel physiology with certain natural molecular indicators and sounds an alarm when mortality due to heatwaves is imminent. Some farmers, if feasible, can expedite harvest and sale; others can choose to take the mussels out of the water for a few days,” he notes.

This solution, however, cannot serve the majority of producers.

“Through a research program funded by the Region of Central Macedonia, our aim is to build a shellfish hatchery, that is, to develop methods of artificial mussel reproduction by selecting more resilient genotypes, which we would then hand over to the state to implement on a much larger scale.” These methods consist of the following and are not related to genetic modification: “What we found through a recently completed PhD is that among millions of mussels, certain genotypes that have evolved through natural selection confer heat tolerance to mussels. This could be done in a targeted way with the help of genetic improvement so that we cultivate more resilient populations that cope better with high-temperature events and lower available oxygen.”

And while AUTh is creating a highly specialized space to develop artificial reproduction methods, the government, unlike the rest of Europe, has not proceeded with the creation of public shellfish hatcheries that would operate for the benefit of producers.

“It’s not some farfetched or outlandish idea, because I can tell you that trout aquaculture operates in exactly the same way. In Northern Greece there are three state fish hatcheries. This would help farmers by providing shellfish spat so they could continue reproduction on their own; it would also lead to the development of other forms of shellfish aquaculture, offering a very good economic incentive to many producers, helping decentralization, and working very favorably for the sector. Unfortunately this is still missing, but I believe and hope it will happen in the future,” adds I. Giantsis.

To the question of what the competent ministries have done to address the situation, the answer was even more disheartening: “It is the responsibility of the government to highlight mussel farming, up until this point it was completely unknown. When I spoke with officials at the Ministry of Rural Development, they told me they didn’t know. They didn’t know that we have a product cultivated in these areas and exported at a rate of 90%, nor that the sectors of mussel and shellfish farming, in a country with this topography and biodiversity, have prospects. So if there is government responsibility, I would focus it here: the lack of knowledge around this part of primary production which most of us also do not know, but we should.”

For Mr. Vervitis matters are now critical in the present, while thoughts about how things might change, if they change at all, concern something very far in the future. For him, producers who lost their income in 2025 must be supported so that they can work again for 2026. Otherwise, as he says, most will abandon their work.

Up next: Prolonged Heat Strains Livestock, Kerkini’s Buffalo Struggle for Water and Relief

The research “The Climate was already bad” was realised with the support of Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung-Office in Greece. Read the complete research here.